The Battle of Adwa (Amharic: የዐድዋ ጦርነት; Afan Oromo: Adwaa; Tigrinya: ውግእ ዓድዋ; Italian: battaglia di Adua, also spelled Adowa) was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The decisive victory thwarted the campaign of the Kingdom of Italy to expand its colonial empire in the Horn of Africa.[3] By the end of the 19th century, European powers had carved up almost all of Africa after the Berlin Conference; only Ethiopia and Liberia still maintained their independence.[4] Adwa became a pre-eminent symbol of pan-Africanism and secured Ethiopian sovereignty until the Second Italo-Ethiopian War forty years later.[5]

In 1889, the Italians signed the Treaty of Wuchale with the then King Menelik of Shewa. The treaty, signed after the Italian occupation of Eritrea, recognized Italy's claim over the coastal colony. In it, Italy also promised to provide financial assistance and military supplies. A dispute later arose over the interpretation of the two versions of the document. The Italian-language version of the disputed Article 17 of the treaty stated that the Emperor of Ethiopia was obliged to conduct all foreign affairs through Italian authorities, effectively making Ethiopia a protectorate of the Kingdom of Italy. The Amharic version of the article, however, stated that the Emperor could use the good offices of the Kingdom of Italy in his relations with foreign nations if he wished. However, the Italian diplomats claimed that the original Amharic text included the clause and that Menelik II knowingly signed a modified copy of the Treaty.[6] The Italian government decided on a military solution to force Ethiopia to abide by the Italian version of the treaty. As a result, Italy and Ethiopia came into confrontation, in what was later to be known as the First Italo-Ethiopian War. In December 1894, Bahta Hagos led a rebellion against the Italians in Akele Guzai, in what was then Italian controlled Eritrea. Units of General Oreste Baratieri's army under Major Pietro Toselli crushed the rebellion and killed Bahta. The Italian army then occupied the Tigrayan capital, Adwa. In January 1895, Baratieri's army went on to defeat Ras Mengesha Yohannes in the Battle of Coatit, forcing Mengesha to retreat further south.

By late 1895, Italian forces had advanced deep into Ethiopian territory. On 7 December 1895, Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael, Fitawrari Gebeyehu and Ras Mengesha Yohannes commanding a larger Ethiopian group of Menelik's vanguard annihilated a small Italian unit at the Battle of Amba Alagi. The Italians were then forced to withdraw to more defensible positions in Tigray Province, where the two main armies faced each other. By late February 1896, supplies on both sides were running low. General Oreste Baratieri, commander of the Italian forces, knew the Ethiopian forces had been living off the land, and once the supplies of the local peasants were exhausted, Emperor Menelik II's army would begin to melt away. However, the Italian government insisted that General Baratieri act. The landscape of Adwa On the evening of 29 February, Baratieri, about to be replaced by a new governor, General Baldissera, met with his generals Matteo Albertone, Giuseppe Arimondi, Vittorio Dabormida, and Giuseppe Ellena, concerning their next steps. He opened the meeting on a negative note, revealing to his brigadiers that provisions would be exhausted in less than five days, and suggested retreating, perhaps as far back as Asmara. His subordinates argued forcefully for an attack, insisting that to retreat at this point would only worsen the poor morale.[7] Dabormida exclaimed, "Italy would prefer the loss of two or three thousand men to a dishonorable retreat." Baratieri delayed making a decision for a few more hours, claiming that he needed to wait for some last-minute intelligence, but in the end announced that the attack would start the next morning at 9:00am.[8] His troops began their march to their starting positions shortly after midnight.

By late 1895, Italian forces had advanced deep into Ethiopian territory. On 7 December 1895, Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael, Fitawrari Gebeyehu and Ras Mengesha Yohannes commanding a larger Ethiopian group of Menelik's vanguard annihilated a small Italian unit at the Battle of Amba Alagi. The Italians were then forced to withdraw to more defensible positions in Tigray Province, where the two main armies faced each other. By late February 1896, supplies on both sides were running low. General Oreste Baratieri, commander of the Italian forces, knew the Ethiopian forces had been living off the land, and once the supplies of the local peasants were exhausted, Emperor Menelik II's army would begin to melt away. However, the Italian government insisted that General Baratieri act. The landscape of Adwa On the evening of 29 February, Baratieri, about to be replaced by a new governor, General Baldissera, met with his generals Matteo Albertone, Giuseppe Arimondi, Vittorio Dabormida, and Giuseppe Ellena, concerning their next steps. He opened the meeting on a negative note, revealing to his brigadiers that provisions would be exhausted in less than five days, and suggested retreating, perhaps as far back as Asmara. His subordinates argued forcefully for an attack, insisting that to retreat at this point would only worsen the poor morale.[7] Dabormida exclaimed, "Italy would prefer the loss of two or three thousand men to a dishonorable retreat." Baratieri delayed making a decision for a few more hours, claiming that he needed to wait for some last-minute intelligence, but in the end announced that the attack would start the next morning at 9:00am.[8] His troops began their march to their starting positions shortly after midnight.

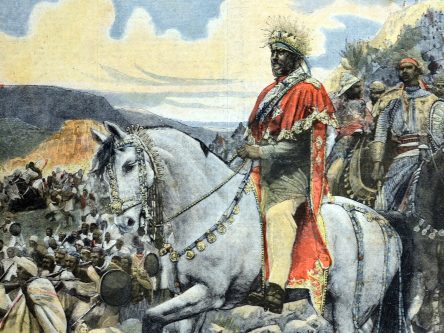

Estimates for the Ethiopian forces under Menelik range from a low of 73,000 to a high of over 100,000 outnumbering the Italians by an estimated five times.[10][11] The forces were divided among Emperor Menelik, Empress Taytu Betul, Ras Welle Betul, Ras Mengesha Atikem, Ras Mengesha Yohannes, Ras Alula Engida (Abba Nega), Ras Mikael of Wollo, Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael, Fitawrari Habte Giyorgis, Fitawrari Gebeyyehu, and Negus Tekle Haymanot Tessemma. Pétridès (as well as Pankhurst, with slight variations) break the troop numbers down (over 100,000 by their estimates) as follows: 35,000 infantry (25,000 riflemen and 10,000 spearmen) and 8,000 cavalry under Emperor Menelik; 5,000 infantry under Empress Taytu; 8,000 Amhara infantry (6,000 riflemen and 2,000 spearmen) under Ras Wale; 8,000 infantry (5,000 riflemen and 3,000 spearmen) under Ras Mengesha Atikem, 12,000 riflemen, 5,000 spearmen, and 3,000 cavalry under Ras Mengesha Yohannes and Ras Alula Engida; 6,000 riflemen, 5,000 spearmen, and 5,000 Oromo cavalry under Ras Mikael of Wollo; 15,000 Shewan riflemen under Ras Makonnen; 8,000 infantry under Fitawrari Gebeyyehu Gora; 5,000 riflemen, 5,000 spearmen, and 3,000 cavalry under Negus Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam.[12] In addition, the armies were followed by a similar number of camp followers who supplied the army, as had been done for centuries.[13] Most of the army consisted of riflemen, a significant percentage of whom were in Menelik's reserve; however, there were also a significant number of cavalry and infantry only armed with lances (those with lances were referred to as "lancer servants").

On the night of 29 February and the early morning of 1 March, three Italian brigades advanced separately towards Adwa over narrow mountain tracks, while a fourth remained camped.[30] David Levering Lewis states that the Italian battle plan called for three columns to march in parallel formation to the crests of three mountains – Dabormida commanding on the right, Albertone on the left, and Arimondi in the center – with a reserve under Ellena following behind Arimondi. The supporting crossfire each column could give the others made the 'soldiers as deadly as razored shears'. Albertone's brigade was to set the pace for the others. He was to position himself on the summit known as Kidane Mehret, which would give the Italians the high ground from which to meet the Ethiopians.[31] However, the three leading Italian brigades had become separated during their overnight march and by dawn were spread across several miles of very difficult terrain. Their sketchy maps caused Albertone to mistake one mountain for Kidane Meret, and when a scout pointed out his mistake, Albertone advanced directly into the Ethiopian positions. Unbeknownst to General Baratieri, Emperor Menelik knew his troops had exhausted the ability of the local peasants to support them and had planned to break camp the next day (2 March). The Emperor had risen early to begin prayers for divine guidance when spies from Ras Alula, brought him news that the Italians were advancing. The Emperor summoned the separate armies of his nobles and with the Empress Taytu Betul beside him, ordered his forces forward. Negus Tekle Haymanot commanded the right wing with his troops from Gojjam, Ras Mengesha in the left with his troops from Tigray, Ras Makonnen leading the center with his troops, and Ras Mikael at the north side leading the Wollo Oromo cavalry. In the reserves on the hills just west of Adwa, were the Emperor Menelik and Empress Taitu, with the warriors of Ras Olié and Wagshum Guangul.[32][31] The Ethiopian forces positioned themselves on the hills overlooking the Adwa valley, in perfect position to receive the Italians, who were exposed and vulnerable to crossfire.

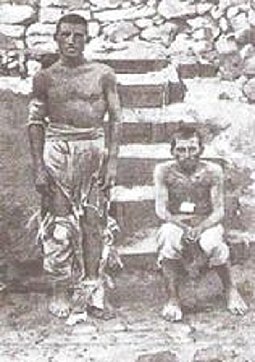

800 captured Eritrean Ascari, regarded as traitors by the Ethiopians, had their right hands and left feet amputated.[44][45] Augustus Wylde records that when he visited the battlefield months after the battle, the pile of severed hands and feet was still visible, "a rotting heap of ghastly remnants."[46] Many mutilated Ascari did not survive. Wylde wrote how the neighborhood of Adwa "was full of their freshly dead bodies; they had generally crawled to the banks of the streams to quench their thirst, where many of them lingered unattended and exposed to the elements until death put an end to their sufferings."[47] Despite some instances of abuse, the Italian prisoners were generally treated better by the Ethiopians. Among the prisoners was General Albertone. Chris Prouty notes that Albertone was given into the care of Azaj Zamanel, commander of Empress Taytu's personal army, and "had a tent to himself, a horse and servants".[48][49] However, around 70 Italian prisoners were massacred in retaliation for the death of Bashah Aboye. The officer responsible for the massacre was reportedly imprisoned by Menelik.

Emperor Menelik decided not to follow up on his victory by attempting to drive the routed Italians out of their colony. The victorious Emperor limited his demands to little more than the abrogation of the Treaty of Wuchale. In the context of the prevailing balance of power, the emperor's crucial goal was to preserve Ethiopian independence. In addition, Ethiopia had just begun to emerge from a long and brutal famine; Harold Marcus reminds us that the army was restive over its long service in the field, short of rations, and the short rains which would bring all travel to a crawl would soon start to fall.[54] At the time, Menelik claimed a shortage of cavalry horses with which to harry the fleeing soldiers. Chris Prouty observes that "a failure of nerve on the part of Menelik has been alleged by both Italian and Ethiopian sources."[55] Lewis believes that it "was his farsighted certainty that total annihilation of Baratieri and a sweep into Eritrea would force the Italian people to turn a bungled colonial war into a national crusade"[56] that stayed his hand. As a direct result of the battle, Italy signed the Treaty of Addis Ababa, recognizing Ethiopia as an independent state. Almost forty years later, on 3 October 1935, after the League of Nations's weak response to the Abyssinia Crisis, the Italians launched a new military campaign endorsed by Benito Mussolini, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. This time the Italians employed vastly superior military technology such as tanks and aircraft, as well as chemical warfare, and the Ethiopian forces were defeated by May 1936. Following the war, Italy occupied Ethiopia for five years (1936–41), before eventually being driven out during World War II by British Empire forces and Ethiopian Arbegnoch guerillas.

After the victory over Italy in 1896, Ethiopia acquired a special importance in the eyes of Africans and black people all over the world alike, as the only surviving African State that successfully defeated a European colonial power in open battle. Italy's government who had viewed them as an inferior barbaric race were brought to their knees and subsequently forced to recognize the African nation of Ethiopia as an equal. After Adowa, Ethiopia became emblematic of African valor and resistance, the bastion of prestige and hope to thousands of Africans who were experiencing the full shock of European conquest and were beginning to search for an answer to the myth of African and black inferiority as well as invoking a strong sense of Pan-Africanism towards to people of African-american origins who had suffered equally appalling injustices at the time and many centuries before.

Input your search keywords and press Enter.